Nicholson Baker’s 1991 long essay U and I on his obsession with John Updike is rife with the smooth, profoundly observational prose which make him one of my favorite fiction writers, though it is also marred by two deficiencies which make it my second-least favorite book of his that I’ve read. (My least favorite is still Room Temperature [which he was completing while writing U and I] because, though the writing is beautiful like his three best works, The Mezzanine, Vox, and The Anthologist in some order, I just don’t care about the premise [a man holding his baby and thinking] because I am not going to have children.)

The first is that Baker claims that women and homosexual men are somehow better suited to writing novels than heterosexual men (and I keep hearing that phrase as “heterosexual white men,” which is hard not to do when thinking of Updike, but to Baker’s credit he doesn’t make that a part of his ridiculous equation). He does admit that he expects to be pilloried for this “sexual determinism,” but mentions it because it is one of the reasons he loves Updike—Updike shows him that heterosexual guys can write fiction, too (137). However, this idea is so, frankly, offensive (1991, everybody!), that it takes away from Baker’s argument that Updike is a genius rather than strengthening it because Baker immediately becomes a less likable persona. The last thing I want to hear as a queer Puerto Rican is how badly heterosexual males have it, especially when the vast majority of authors that have been taught in literature classes (especially when Baker would have been in college) are male.

The second is that it becomes apparent by the end of the book that a significant part of Baker’s motivation for writing it is his own insecurities as a writer. He is haunted by the question of whether he is or will be as good as Updike (for the record, twenty years on I think he’s better than Updike, and I sometimes teach his books while never teaching Updike’s), and while it is legitimate for him to ask this question, it is not one I am interested in reading about because all writers, myself included, have a version of this anxiety. Am I good at all? Is this just a waste of time? Et cetera. Perhaps this element of the book is less onerous to non-writer readers.

Nevertheless, with those two important exceptions, there are some delightful elements of U and I. Here are a few of my favorites:

There is a brief discussion of masturbating to Updike’s sex scenes (19). Baker says that he has not, though he knows people who have. I must admit that one of the elements of Updike’s work which first drew me to him was the eroticism included in his fiction because he happened to be one of the first writers I encountered who wrote openly about sex (the description of the bikinied teenager in his short story “A&P” [which I did, indeed, teach once myself]—so hot when I found it in high school). But fifteen years later his work is laughably vanilla to my jaded tastes.

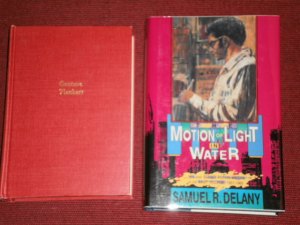

There are several moments when Baker makes comments about book culture that are delicious. This is my favorite aspect of his writing: it is clear that he loves books as objects as much as I do, and thus pays attention to his interactions with them. For instance, he mentions that in college he would throw the dust jackets of his hardcovers away, wanting them to look like the unjacketed books in college libraries (29). I seriously considered doing this when I was in college, too! But I am now very glad that I never started this practice, and hope that Baker has stopped it. Dust jackets are fun to look at because they vary so widely, and they make finding books on the shelf much easier. Baker also mentions accumulating different editions of books he already has when he encounters them in used bookstores, as I do. Here is his sublime description of the Franklin Library edition of Updike’s Rabbit, Run: “The padded, bright red binding was somewhat more reminiscent of a comfortable corner booth at an all-night, all-vinyl coffee shop” (36). There is also a passage where Baker describes removing the price sticker from books and then putting “it back on because it is a piece of information I will always want to have” (73). Aside from old price stickers on the occasional used book that I acquire, I hate price stickers and always remove them, but I appreciate Baker’s desire to know as much about the object as possible, to remember the individual volume’s history (how much was a copy of Madame Bovary going for in year X?).

Baker observes that “[b]ooks and life interpenetrate” (125), which is exactly correct, and is why reading books is so necessary and enjoyable. They teach us about life and how to live it better. This is why I love Baker’s fiction so much; his ability to observe the minutia of life (including our physical interactions with books) and show its importance is unparalleled.